The all-time leading scorer among women in Division I college hoops is Wichita native Lynette Woodard. Woodard scored 3649 points in her four year career at Kansas using a men’s sized basketball and without a three point circle. But look up the NCAA record book for women’s basketball and Lynette Woodard is not listed in the top 25 career scorers. In fact, she’s not listed at all. The list shows University of Washington star Kelsey Plum at 3527 points as the record holder, yet Plum is 122 points shy of Woodard’s point total.

Although Woodard is the all-time leading scorer in Division I women’s basketball, a quirk in the NCAA record-keeping system omits her. The NCAA took control of women’s collegiate hoops in the 1981-82 season, one year after Woodard graduated from Kansas. Before that time women’s college basketball was controlled by the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women.

Next year, University of Iowa phenom Caitlin Clark is likely to zoom past both Kelsey Plum (she is 810 points short) and Woodard (932 points). But before Clark gets her moment in the sun, it is important to acknowledge those who made Caitlin Clark’s journey possible.

Title IX, passed by the Congress and signed by President Nixon in 1972, required equal opportunity for women in any educational endeavor which received federal funds. It took another five years before the Office of Civil Rights issued the regulations for sports. “When the NCAA saw that federal money would be going to the AIAW, they took control of it,” said Marlene Mawson, who is sometimes referred to as the “Mother of Women’s Sports Programs at KU.” The NCAA decided that women’s sports records don’t count unless the woman played at least three years under the NCAA umbrella. Woodard played under the AIWA’s umbrella all four years.

The AIAW was set up like the NCAA, with Division I, Division II, and Division III schools. And Woodard scored more career points than anyone at a Division I school in either the AIAW or the NCAA. Her unrecognized scoring record has stood for 42 years.

It was harder to score points in Woodard’s day. Although she played in a major conference, the Big 8, and competed in the national tournament against programs like Connecticut, Old Dominion and Tennessee, two rules made it harder for Woodard to get to 3649.

Woodard had no three point circle

Woodard slowly got to 3649 points one and two points at a time. The only three point play was scored the old fashioned way–by being fouled while making a basket.

When I met Woodard recently, I asked her twice: “How many of the field goals you made at KU would be three-pointers today?” She wouldn’t answer. “We weren’t setting up our offense to exploit the three point line. At that time, if you shot from the top of the key, you were considered a hot dog,” she explained. Still, she allowed that she made a lot of baskets from the corners, and some from the top of the key.

Because Pistol Pete Maravich, the longtime men’s career scoring king, also played without the benefit of a three point line, it has become a virtual cottage industry in Louisiana to guess how many points The Pistol would have scored with a three point circle. Unlike Woodard, Pistol Pete was a natural showman, and he had no fear of being accused of being a hot dog. Like Woodard, he made a lot of baskets that would be three pointers today. Former LSU Coach Dale Brown estimates that Maravich would have averaged 13.3 three-pointers a game.

The NCAA adopted a three-point circle for women’s basketball in the 1987-88 season, long after Woodard graduated from Kansas. 38% of Kelsey Plum’s field goals were three-pointers, and Caitlin Clark makes 40% of her three-point attempts.

Woodard set her record using a men’s-sized basketball

The smaller basketball for women was introduced in the fall of 1984. The men’s basketball that Woodard played with at KU was size 7, with a circumference of 29.5″. The smaller women’s ball is a size 6, with a circumference of 28.5″. Although Woodard could palm a men’s basketball, playing with a smaller women’s basketball would have added to her dribbling, passing and scoring prowess.

Woodard takes the injustice in stride

I met Woodard for the first time recently. Even though I was a year behind her at KU, I didn’t have the guts to go up to her on campus and introduce myself. I didn’t know you could. She was, to me, otherworldly. But after meeting Woodard she put me at ease with her humility.

Growing up in Kansas, I was keenly aware of the Woodard legend. At Wichita North High School, nobody could stop her from scoring, not even the boys. “I was in gym class with Lynette,” says Marsha (Miller) Gillenwater, a schoolmate of Woodard’s at North High. “Before our girls gym class started, three or four guys would try to stop her from scoring, and she mowed them down. She would play against all four guys at a time and dominated them.” The stories of men players (often two or more) challenging Woodard to a pickup game and losing are legion.

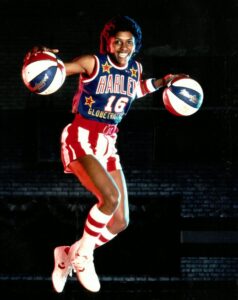

I asked Woodard about the pre-gym class beat down of the boys. “I wasn’t going to let them get in my way,” she says. But she never brags. Instead, she constantly talks about her indomitable will to win, to overcome any obstacle. She doesn’t say: “I helped the USA win our first gold medal in women’s basketball in the Olympics in LA in 1984,” or “I was the first female Harlem Globetrotter.” Everyone already knows these things. Instead of talking about her successful outcomes, she talks about the process, the can-do attitude.

Where did Woodard get this never-say-die resilience? When her accomplishments are discussed, she credits everyone but herself: God, her brother, her mother, her teammates, etc. The most striking things about her are her charisma, her beauty, and her humility. In some ways, she looks younger than ever. Her brilliant smile and infectious optimism are stunning. Her charisma is Muhammad Ali-like, without the boasting. How did a girl born in 1959 do so many things that no woman had ever done before?

Woodard’s childhood dreams were bigger than life

Woodard dreamed of becoming the first female Harlem Globetrotter at age age 7, in 1966. Do you have any idea how crazy that is? In 1967, the Olympics did not even have Women’s Basketball. Nor did most American high schools or colleges. Women’s competitive basketball was not a “thing” in 1967.

The 1976 Olympics was the first time the Olympics featured women’s basketball. Ann Meyers and Nancy Lieberman were on that first squad, and the U.S.S.R. dominated, crunching the USA 112-77. Marlene Mawson explained the evolution of women’s sports in the USA: “During the Cold War, Russia was dominating women’s Olympic sports. Under President Kennedy, the U.S. started five Olympic training centers around the country to help us compete against the U.S.S.R,” she said.

Woodard had a cousin, “Geese” Ausbie, who was a legendary Harlem Globetrotter. “He lived about two hours away, in Oklahoma,” says Woodard. “I would see him at family gatherings, cookouts,” she says. But the problem is there was not a female Harlem Globetrotters team. So her dream was impossible. Yet she kept a poster of the Harlem Globetrotters above the door in her bedroom.

In winter months, she and her brother invented an indoor basketball game called “Sock Ball.” They would use a pair of rolled up socks and they made a makeshift nerf-like hoop, and used the kitchen timer as the game buzzer. Her brother still lives in Lynette’s childhood home in Wichita.

The KC-135 tanker that crashed in her neighborhood

Woodard cheated death on a cold Saturday morning, January 16, 1965. She was six. A U.S. Air Force Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker took off at Wichita’s McConnell Air Force Base, carrying 31,000 gallons of jet fuel. The plane was doing routine maneuvers. An unscheduled autopilot malfunction involving the rudders occurred; the pilot was unable to reverse it. A piece of the tail fell off, and the nose dove and crashed in an African-American neighborhood in Wichita, barely missing Woodard’s childhood home.

The crash killed all seven crew members, and 23 members of the neighborhood. Additionally, at least 27 people on the ground sustained injuries. “My brother was drenched in jet fuel,” says Wichita luminary Lavonta Williams, a former City Councilwoman and Wichita School Board member. Woodard lost a close friend childhood friend in the crash.

Had Woodard followed her normal Saturday morning routine that day, she might have perished. Most Saturdays she went over to play with her friend who was killed. But the night before, Woodard’s grandmother, living a couple of blocks east of the crash, asked her to spend the night. Woodard heard a loud airplane noise getting closer and closer and heard and felt a thunderous explosion. Her grandmother’s house shook. She looked out the window and it was hell on earth.

The G.O.A.T?

Woodard has no interest in comparing herself to other great women hoops players. The most that can be said is that one was the best player at their time, not the best player of all time. But Woodard remains the uncrowned all-time Division I scoring queen, although few know about her accomplishment. Any discussion of “Who was the greatest female basketball player of all time?” would naturally include Woodard. But she isn’t interested in such accolades. She showed the USA what the women’s game would become. And perhaps her biggest accomplishment was winning the contest to become the first female Harlem Globetrotter in 1985.

Caitlin Clark

Caitlin Clark will be a senior this fall, and she is likely to break Kelsey Plum’s official record of 3527 points, and Woodard’s unofficial record of 3649. Woodard would be pleased. The women’s game has evolved, and the sport is more popular than ever. The sport has come a long ways since a little girl in Wichita dreamed of being a Harlem Globetrotter.

Excellent. You nailed it!!!

Excellent article. So much credit to be given this amazing and talented athlete. Thanks for drawing attention to her.

As a KU grad, it is a shame that Woodward isn’t on the NCAA all time list, and there isn’t even a mention on the list in Wikipedia. Hopefully if Clark passes her number she will acknowledges that Lynette had the real record.

Agreed!! I’ve been scouring the internet for info on this, with Clark so close. Just barely any mention. Sad.

I played high school ball with Lynette at North. She was absolutely something. Our gym was like a pit-bleachers above the gym floor. Gawd I can still remember running those stairs. At the end of practice when the rest of us were hitting the showers, Wood was hitting the stairs alone. And, she is exactly as this article stated-she is just good people.